Background

Cardiac arrest remains one of the leading causes of death in the United States and is frequently encountered in the emergency department (ED). It is defined as cessation of cardiac function and lack of circulation. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) improves outcomes especially if it is performed within minutes of cardiac arrest. According to recent American Heart Association (AHA) statistics, approximately, 10.6% of patients who experience cardiac arrest survive to hospital discharge [1]. On the other hand, pulseless electrical activity (PEA) is a form of cardiac arrest in which patients continue to have organized cardiac electrical activity without a palpable pulse. This patient population's overall survival is much lower with 2.4% of patients surviving to hospital discharge [2]. Until recently, there has been an incomplete understanding of the the term PEA and what this means physiologically. With the advent of ultrasound (US), there has now been elucidation of two forms of PEA. True-PEA (tPEA) which lacks cardiac activity on US, has poor survival rates, while pseudo-PEA (pPEA) which demonstrates some cardiac activity on US, shows improved survival, potentially due to altering standard ACLS protocol driven management. The following study specifically looks at the data evaluating the predictive value of US in patients presenting in cardiac arrest with PEA.

Clinical Question

Does bedside US predict the restoration of spontaneous circulation in patients with pulseless electrical activity?

Methods & Study Design

- Design

- Systematic review and meta-analysis

- Data from MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane library databases (inception to June 2017)

- Statistical analysis

- Review Manager 5.4 and Stata 12

- I2 statistics to assess heterogeneity

- Random effects model for all polled outcome measures

- Begg’s test for publication bias

- Study Eligibility Criteria

- Adults with PEA

- Cardiac US was used to detect cardiac activity

- ROSC defined as primary outcome

- Prospective/ observational studies

- Written in English

- 2x2 contingency table can be formed from data

Results

Included Studies

-

- 11 studies with 777 patients with PEA included

- 230 patients had ROSC

- 42/343 "true-PEA" patients had ROSC

- 188/434 "pseudo-PEA" patients had ROSC

- Patients with pPEA were 4.35x more likely to experience ROSC than those tPEA (Risk ratio 4.35, confidence interval 2.20-8.63, p<0.00001, significant statistical heterogeneity I2= 60%)

Limitations

-

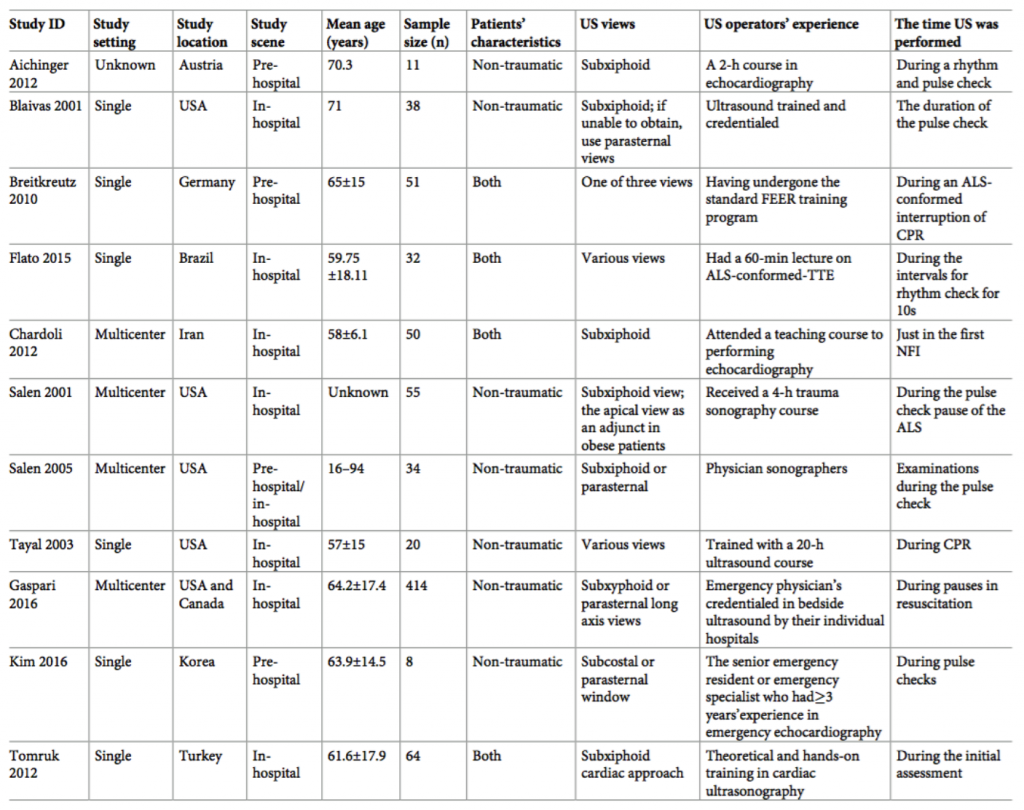

- Significant heterogeneity amongst the 11 studies

- 4 studies enrolled both trauma and non-trauma patients

- In 3 studies, US evaluation occurred in the pre-hospital setting

- Large confidence interval

- Small pooled sample size

- Varying protocols and US views used in different studies to determine cardiac activity

- Varying definition of ROSC between studies

- Significant heterogeneity amongst the 11 studies

Authors Conclusion

"In cardiac arrest patients who present with PEA, bedside US has an important value in predicting ROSC. The presence of cardiac activity in PEA patients may encourage more aggressive resuscitation. Alternatively, the absence of cardiac activity under US could be promoted as a way of confirming a poor prognosis and used to support the decision to terminate resuscitative efforts."

Our Conclusion

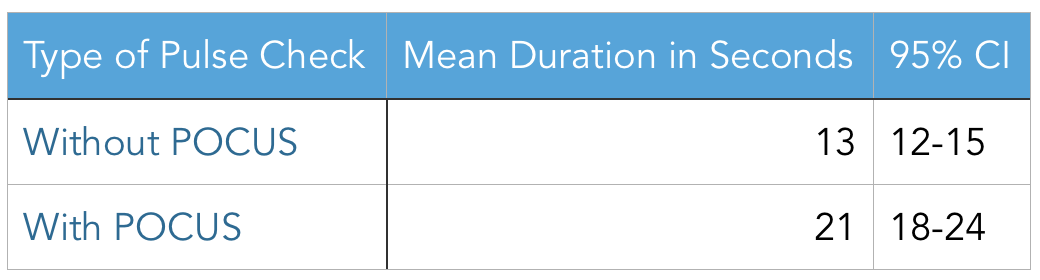

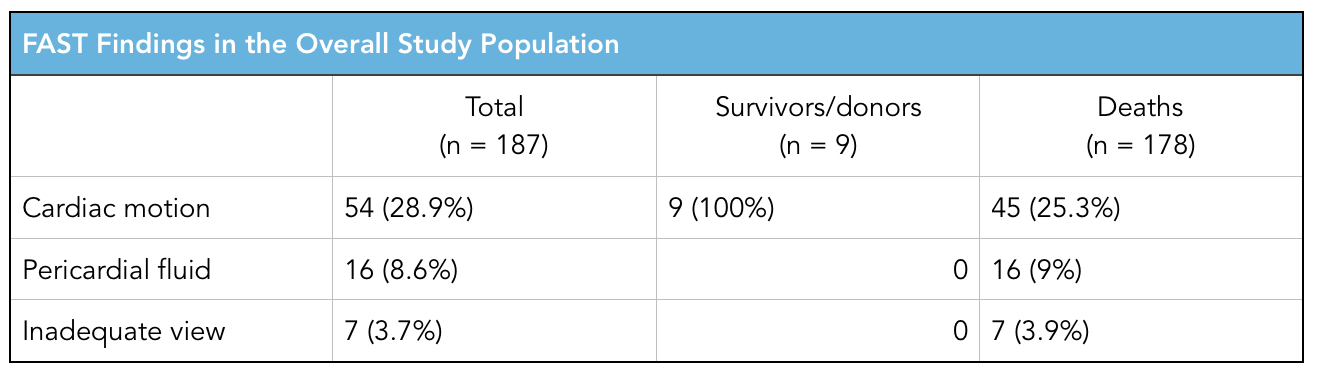

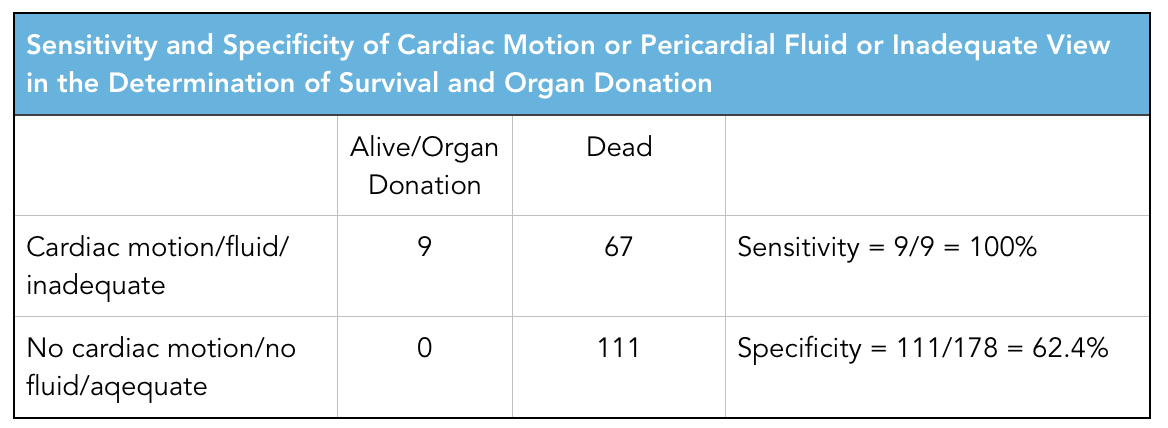

This study found that patients in cardiac arrest with pPEA (i.e. cardiac motion on ultrasound) have higher ROSC than those with tPEA (i.e. no cardiac motion on ultrasound). The exact risk ratio for ROSC quoted in their results should be interpreted with caution since this meta-analysis included studies with vastly different characteristics. The 11 studies included took place in 9 different countries over the span of 15 years, included different US views (subxiphoid, parasternal), varied settings (pre-hospital and in-hospital US studies), varied patient populations (some studies included traumatic cardiac arrest) and had varying US operator experience. Additionally, other factors such as time to initiation of CPR, length of CPR, and the previous health of the patient were not accounted for. These limitations can affect the accuracy of the risk ratio presented in this study. That being said, even with significant heterogeneity in this study, resulting in a very wide confidence interval, the lower limit of the risk ratio (2.20) still finds statistical significance for higher rate of ROSC in patients with pPEA compared to patients with tPEA.

This study essentially confirms what is already known from previous data (specifically the Gaspari study which represents the majority of patients in this meta-analysis) but fails to address the big question of "Does US guided resuscitation provide a mortality benefit in the management of cardiac arrest?" This is a complex question that takes into account multiple other questions including the debate over US increasing interruptions in chest compressions, the use of US to identify immediately reversible causes of cardiac arrest (i.e. tamponade, massive PE) , the true definition of cardiac standstill (which calls the results of all cardiac arrest studies thus far into questions), and ultimately, can US be used to determine if further resuscitation is futile? As with all advances in technology, finding the right niche to benefit the patient is of upmost importance and at this point in time, the utility of US in cardiac arrest remains to be determined.

The Bottom Line

Bedside ultrasound can be used to determine pPEA from tPEA in patients with cardiac arrest. This may help guide resuscitation efforts as patients with pPEA have increased rates of ROSC.

Authors

This post was written by Tina Vajdi, MS4 at UCSD. Review and further commentary was provided by Michael Macias, MD, Ultrasound Fellow at UCSD.

References

-

- Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, Arnett DK, Blaha MJ, Cushman M et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2016 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2016; 133(4):e38– e360. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000350 PMID: 26673558

- Engdahl J, Bang A, Lindqvist J, Herlitz J. Factors affecting short- and long-term prognosis among 1069 patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest and pulseless electrical activity. Resuscitation 2001; 51 (1):17–25. PMID: 11719169

- Gaspari R, e. (2018). Emergency department point-of-care ultrasound in out-of-hospital and in-ED cardiac arrest. - PubMed - NCBI . Ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 20 April 2018, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27693280