Background

The FAST exam is a useful tool in screening for the presence of intraperitoneal free fluid in the setting of trauma. The utilization of ultrasound provides rapid imaging in the trauma bay that can help guide clinical decision making and the necessity for surgical intervention. The FAST exam is comprised of subxiphoid, right upper quadrant, left upper quadrant, and suprapubic views by ultrasound. Previous research has indicated that the RUQ, specifically the hepato-renal space (Morrison’s pouch), is the preferred area for the detection of free fluid.1,2 However, scarce research into the sub-divisions of each view has been performed.

Clinical Question

The aim of this study was to determine what specific sub-divided areas of each FAST view were the most sensitive in the detection of intraperitoneal free fluid.

Methods & Study Design

• Design

This was a retrospective cohort analysis.

• Population

All patients who received a FAST exam at a single Level 1 trauma center over an 18-month period.

• Intervention

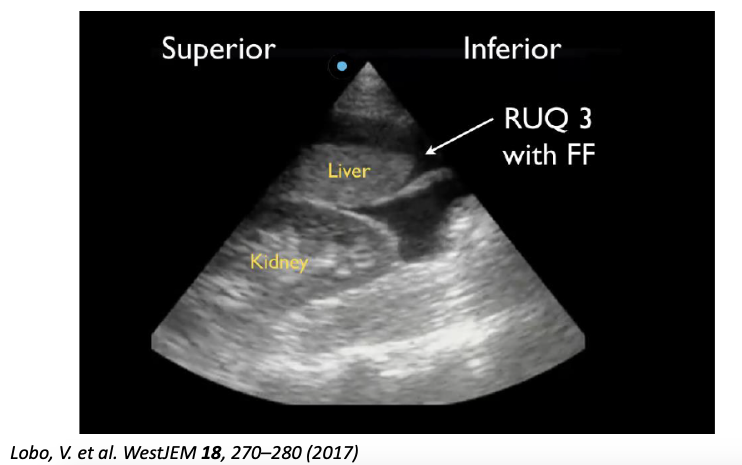

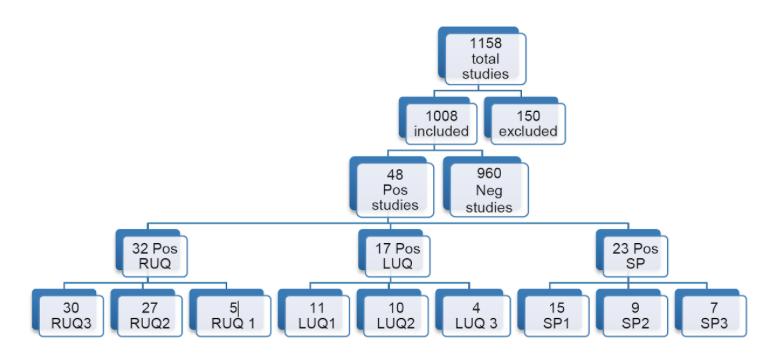

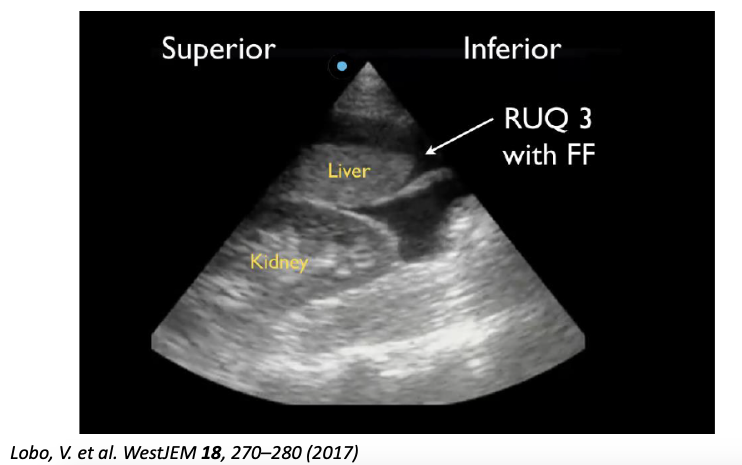

The RUQ, LUQ, and suprapubic views of the FAST were each subdivided into three additional sections for analysis. Specifically, the RUQ was divided into the hepato-diaphragmatic space (RUQ1), hepato-renal space (Morrison’s pouch) (RUQ2), and the caudal liver tip (RUQ3). The LUQ was divided into the spleno-diaphragmatic space (LUQ1), the spleno-renal space (LUQ2), and the inferior pole of the kidney (LUQ3). The suprapubic area was divided into the lateral sides of the bladder (SP1), posterior bladder and anterior pelvic organ space (SP2), and posterior uterus (in female subjects) (SP3). The subxiphoid view was excluded as the study was only interested in intraperitoneal free fluid.

• Outcomes

Each sub-quadrant of all positive FAST exams was analyzed for the presence of free fluid.

Results

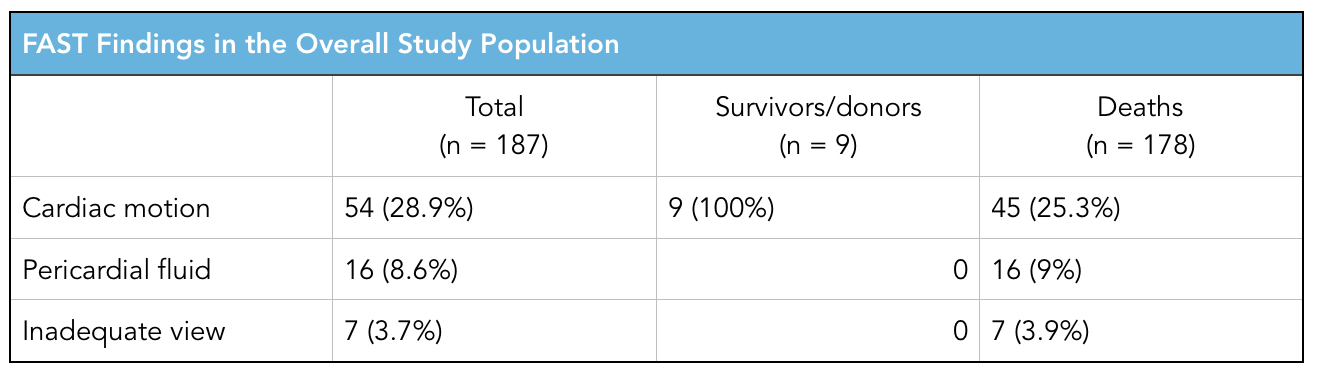

- Of the 1,008 FAST scans included in the study, 48 (4.8%) were positive for free fluid. These findings were either confirmed by CT or intraoperatively.

- Of the positive FAST exams, 32 (66.7%) were positive in the RUQ, 17 (35.4%) were positive in the LUQ, and 23 (47.9%) were positive in the suprapubic region.

- Of the positive RUQ scans, 30 (93.8%) were positive in RUQ3, 27 (84.4%) in RUQ2, and 5 (15.6%) in RUQ1.

- Of LUQ scans, 11 (64.7%) were positive in LUQ1, 10 (58.8%) in LUQ2, and 4 (23.5%) in LUQ3.

- In the SP view, 15 (64.7%) were positive in SP1, 9 (58.8%) in SP2, and 7/9 (77.7%) in SP3.

- No correlation was found between quadrants.

Strength & Limitations

This was a simple, well done study that provides useful information on the FAST exam. The study featured a relatively small sample size of 48 positive FAST exams. There is a potential that in the time between a FAST exam and further intervention (CT or OR) further bleeding could have occurred, thus lowering the sensitivity of the FAST. The authors struggled to make conclusions regarding the suprapubic view between sexes due to a small sample size of positive SP views.

Authors Conclusion

The caudal tip of the liver (RUQ3) is the most sensitive area for the detection of free fluid on FAST exam.

Our Conclusion

The FAST exam can be an extremely useful tool at the bedside or in the setting of trauma. All areas of the FAST should be properly viewed, with particular emphasis on the caudal tip of the liver. It is important to note that many FAST exams only showed free fluid in one area of one quadrant while showing no free fluid elsewhere, therefore it is important to assess all three areas in every view to increase the sensitivity of the FAST exam.

The Bottom Line

Despite previous emphasis on Morrison’s pouch, the caudal liver tip is a more sensitive indicator of intraperitoneal free fluid and should be properly visualized on every FAST exam.

Authors

This post was written by Oliver Marigold, MS4 at UCSD School of Medicine, Charles Murchison MD and Amir Aminlari MD.

References

- Von Kuenssberg Jehle, D., Stiller, G. & Wagner, D. Sensitivity in detecting free intraperitoneal fluid with the pelvic views of the FAST exam. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine 21, 476–478 (2003).

- AIUM Practice Guideline for the Performance of the Focused Assessment With Sonography for Trauma (FAST) Examination. Journal of Ultrasound in Medicine 33, 2047–2056 (2014).

- Lobo, V. et al. Caudal Edge of the Liver in the Right Upper Quadrant (RUQ) View Is the Most Sensitive Area for Free Fluid on the FAST Exam. WestJEM 18, 270–280 (2017).