Background

Pulmonary embolism (PE) is a disease entity with a high mortality rate, ranging from 2.5-33%. Frequently, its diagnosis is delayed or frankly missed and often it is only discovered during autopsy. Around 66% of deaths occur during the first hour of presentation and 75% of deaths during the initial hospitalization. The mechanism of morbidity/mortality for PE is thought to be secondary to right ventricle (RV) outflow obstruction, leading to circulatory collapse. Delays in diagnosis have been linked to issues with imaging (wait times, schedules), contrast in the setting of renal impairment, and poor IV access.

In the emergency department, it is not only critical to identify patients with PE, but also to identify those who are at risk for decompensation and poor outcomes. This can be accomplished by evaluating for signs of RV dysfunction which has been associated with RV failure, hemodynamic collapse, and death. Previous studies have shown that right ventricular dysfunction has been found in 27-40% of normotensive patients with PE. Well studied markers of RV dysfunction include elevated biomarkers [1], specific ECG findings (RBBB, tachycardia, S1Q3T3, anterior TWI, ST elevation aVR, atrial fibrillation) [2], and RV dysfunction on echocardiography [3]. While biomarkers and ECG are readily available to emergency providers (EP), these are less specific for the diagnosis of PE and bedside echocardiography may prove to be more useful for evaluation of PE and RV dysfunction.

Clinical Question

Does evaluation for right ventricular dilation by emergency physicians using bedside echocardiography add diagnostic value in the evaluation for suspected pulmonary embolism?

Methods & Study Design

- Design

- Prospective observational study

- Population

- Using a “convenience sample” population of patients who presented to the ED at Boston Medical Center from June 2009 – August 2011, with a moderate to high suspicion (pretest probability) of having a PE. Wells score ≥2, those receiving PE imaging (CT, angio, V/Q scan), or those who came in with diagnosis of PE.

- Exclusion criteria

- Non-english speakers

- Prisoners

- Intervention

- Transthoracic echocardiography (blinded of confirmatory results) was performed by 4 ED docs, 1 with advanced training in cardiac sonography. The other 3 had standard 1-month residency rotation in ultrasound and a minimum of 25 cardiac ultrasounds; plus, 10 hours hands-on and 10 hours image review with principal investigator.

- Data collection

- 3 views recorded: parasternal short & long axis, and apical 4-chamber, with primary measurement being qualitative assessment of RV size vs. LV size. Normal ratio (0.6:1)

- Dilation defined as >1:1 RV:LV ratio

- RV length and diameter or qualitative distension of RV apex adjacent to LV apex also assessed

- They also recorded: RV function (nl vs. hypokinetic), paradoxical septal motion, and presence of McConnell’s sign.

- All image reads were reviewed by the PI.

- ED RAs then used chart review to compare findings to confirmatory imaging

- PE was categorized as proximal vs distal

- Disposition of patient was also documented

- 3 views recorded: parasternal short & long axis, and apical 4-chamber, with primary measurement being qualitative assessment of RV size vs. LV size. Normal ratio (0.6:1)

- Outcomes

- Diagnostic characteristics

- Sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV, positive and negative likelihood ratios

- Presence of advanced signs of RV dysfunction

- Right ventricular hypokinesis [qualitatively assessed as normal or hypokinetic], paradoxical septal motion, and McConnell’s sign

- Diagnostic characteristics

Results

-

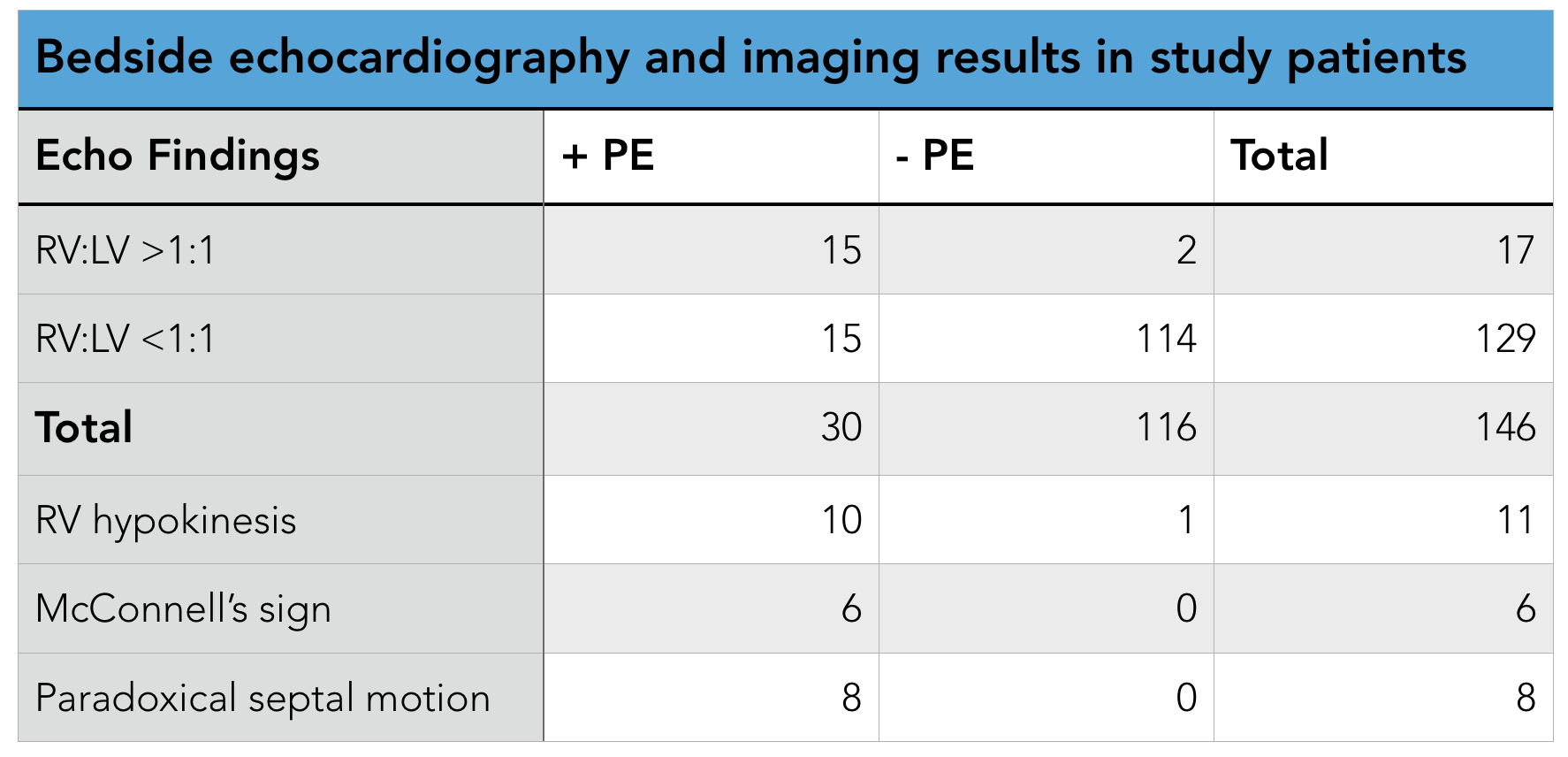

- Final analysis

- 146 patients included in study

- 126 with moderate pretest probability

- 20 with high pretest probability

- 126 with normal RV:LV ratio, 17 with increased RV:LV ratio

- 30 had PE, of these 15 also had increased RV:LV ratio

- Presence of RV dilation test characteristics

- Sensitivity 50% (95% CI 32% to 68%)

- Specificity 98% (95% CI 95% to 100%), a positive predictive value of 88%

- Positive Predictive Value 88% negative predictive value of 88%

- Negative Predictive Value 88% (95% CI 83% to 94%).

- Positive Likelihood Ratio 29 (95% CI 6.1% to 64%)

- Negative Likelihood Ratio 0.51 (95% CI 0.4% to 0.7%)

- Good observer agreement 96%, independent 100%

- Final analysis

Strengths & Limitations

- Strengths

- Good concordance of sens/spec with prior study observations, although higher sensitivity

- Good intra-observer agreement/reliability

- Limitations

- Single location, young population (less chronic diseases leading to RV changes)

- Operator skill may not generalize to other physicians, other EDs. PI was very experienced sonographer.

- Convenience sample leading to possible selection bias.

- Secondary outcomes under-powered.

Author's Conclusions

The authors conclude that right ventricular dilatation on bedside echocardiography may help emergency physicians rule in pulmonary embolism more rapidly by raising a provider’s index of suspicion before definitive testing. They also note that this evidence supports the concept that patients with a moderate to high pretest probability for pulmonary embolism and a bedside echocardiography result showing right ventricular dilatation should be considered for anticoagulation before definitive testing.

Lastly, they also comment on severity of PE, noting that patients with signs of advanced right ventricular dysfunction on bedside echocardiography (right ventricular dilatation with right ventricular hypokinesis, McConnell’ s sign, or paradoxical septal motion), tends to occur in patients with a larger clot burden who are more likely to be admitted to an ICU setting or have in hospital mortality (though this study was not powered appropriately for this analysis).

Our Conclusions

We agree with the author's conclusions of this study that EP performed bedside echocardiography is a useful adjunct in the evaluation of suspected PE, both in identification of PE as well as risk stratification. We know that delays in diagnosis/treatment can lead to worse outcomes, however with the ability of EPs to perform bedside echocardiography and identify right ventricular dilation, this may reduce the time to both of these endpoints. It also seems reasonable that in patients who are moderate to high risk for PE, whom have evidence of right ventricular dilation on bedside echocardiography, be empirically treated with anticoagulation prior to definitive imaging, with the caveat that they have no high bleed risk.

The Bottom Line

Emergency physician performed bedside echocardiography can be used reliably to increase provider's index of suspicion for PE in patients demonstrating RV dilation; however, given its poor sensitivity, it should not be used as a screening tool for PE.

Authors

This post was written by Hector Guerrero, MS4 at UCSD. It was reviewed by Michael Macias, MD, Ultrasound Fellow at UCSD.

References

-

- Weekes AJ, e. (2017). Diagnostic Accuracy of Right Ventricular Dysfunction Markers in Normotensive Emergency Department Patients With Acute Pulmonary Embolism. - PubMed - NCBI. Ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 25 September 2017, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26973178

- Shopp, J., Stewart, L., Emmett, T., & Kline, J. (2015). Findings From 12-lead Electrocardiography That Predict Circulatory Shock From Pulmonary Embolism: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Academic Emergency Medicine, 22(10), 1127-1137. doi:10.1111/acem.12769

- Dudzinski DM, e. (2017). Assessment of Right Ventricular Strain by Computed Tomography Versus Echocardiography in Acute Pulmonary Embolism. - PubMed - NCBI . Ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 25 September 2017, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27664798

- Dresden S, e. (2017). Right ventricular dilatation on bedside echocardiography performed by emergency physicians aids in the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism. - PubMed - NCBI . Ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 25 September 2017, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24075286